WATERWORLD

December 10, 2023

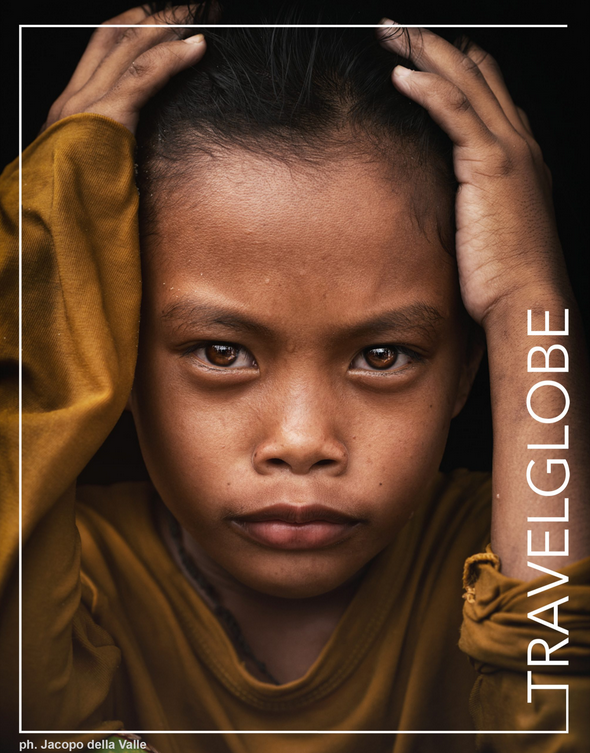

The Bajau are indigenous, nomadic and stateless people known as “Sea Gypsies”, who live off the coasts of the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Their nomadic origins make them difficult to approach and get to know. They are wary people because they are used to living isolated, they are often treated with indifference or denounced because they are considered illegal immigrants on the mainland. In fact, they are not recognized as citizens by any state and have no fundamental rights. In the past they moved freely across the seas of Southeast Asia; today they are more sedentary while they still live closely linked to the sea, far from the coast and its society.

Historical sources report that the Bajau are descended from the royal guard’s soldiers of the Sultanate of Johor who, after the fall of the Sultanate of Malacca, migrated from the southern coasts of the Philippines and settled along the eastern coast of Borneo following severe storms.

Paralleling these historical sources, “The legend of the Princess of Johor” tells of a sudden and extremely violent flood that hit Malaysia thousands of years ago. During this cataclysm the princess was dragged by the impetus of the currents so her father, afflicted by pain, ordered his subjects to go to sea in search of his daughter and return only when they had found her. Even today the descendants of that people continue the search for their princess, moving into the sea as nomads.

The Bajau are divided into three groups: the tribes who live on the islands, those who live in the villages of wooden stilt houses in the open sea or the Bajau Laut who spend their whole life in wooden boats called “lepas”, only 5 meters long and 1.5 meters wide.

Salis is a fisherman who took me to several seaside Bajau villages, showing me their way of life and translating their language.

Salis moved to the mainland a few years ago to work in the city, but after a few months he ran away to go back to live in his stilt house, because he couldn’t adapt to that “regular” life away from the sea.

How to blame him … his house is located in a heavenly place within the marine park “Tun Sakaran”, surrounded by transparent water, coral reefs and a rich biodiversity of marine species.

The construction of one stilt house takes about two months of work and takes place during the low tide period. Each stilt house consists of a single room, where live up to 8 people of the family: they sleep on the floor or in hammocks, cook and eat together.

Rosita, Salis’ wife, piqued my curiosity with her yellow face, sprinkled with “Burak”: a traditional dough whose main ingredients are rice flour and turmeric root. Burak, similarly to the Burmese “Thanaka”, is used as a sunscreen to protect the skin from sunburn.

Children have been swimming since they were born and play continuously and fearlessly in the water, use aluminum tubs as boats, collect starfish or follow their fathers in fishing for small fish.

I’ve been on several fishing sessions with Salis and his friends, realizing that the Bajau have unmatched ocean knowledge and are all expert freedivers.

A 2018 scientific research showed that Bajau spleens are about 50% larger than those of a neighboring terrestrial group (the Saluan): they store more blood rich in hemoglobin, which is expelled into the bloodstream when the spleen contracts in depth, thus resulting in greater resistance during freediving.

Fishing and collecting shells and shellfish are the only activities that the Bajau do, even for 8 hours a day, and they are able to go down to depths of 30 meters to catch pelagic fish or look for pearls and sea cucumbers.

Despite being skilled freedivers, they have to deal with nitrogen narcosis, hypothermia and decompression sickness which can sometimes have fatal consequences: being stateless, they are not entitled to health care and cannot access the treatments that would allow them to survive.

The Bajau only reach the mainland to sell their products, exchange them for water, rice and tobacco or to shelter from too strong storms.

Unfortunately, however, their life at sea is changing and they are becoming increasingly dependent on society and its money market, such as for example the petrol engine and the thoughtless use of plastic objects. During my stay in the Bajau villages I was sad to note that often the beaches and the sea were littered with garbage. While in the past the production of organic waste by sea nomads was not a problem, today the growing increase of plastic and non-biodegradable materials contributes to the pollution of the ecosystem in which they live.

The low level of education, the presence of daily problems such as the tightening of controls, the gradual decline of the fish and the restrictions on their movements, have not yet allowed the Bajau to develop an environmental awareness.

For now, moving to the mainland is not an option, and I hope they will manage to live in harmony with the beautiful nature that surrounds them, finding a balance between the rights and duties of modern society and the preservation of their traditions and lifestyles.

This photo-story was awarded by Travel Tales Award 2023 as the best project . My “WATERWORLD” portfolio was published on the 110th Edition of TravelGlobe Magazine on December 2023.